For a background of the ins and outs of what Chronic Fatigue is check out Part 1

Managing Chronic Fatigue is hard, it’s hard for the sufferers. Plus, for those fortunate enough to have Income Protection, it’s hard for the case managers as well, because neither really knows their true work capacity, or, often, what to do about it.

We’ve been working with chronic fatigue cases under Income Protection for the last few years, with clients newly diagnosed to clients who had been suffering for years on end. Referrals for both primary and secondary fatigue are growing exponentially. Why? Because we are getting results. We are supporting their recovery and their successful conditioning for work and life.

Check out our quick 80 second video summarising this: Specialised Health on Exercise Physiology for Fatigue Management

So, as promised, for Part 2 we’re diving deeper into the management of chronic fatigue…

MANAGING CHRONIC FATIGUE WITH EXERCISE – THE G.E.T (Graded Exercise Therapy) DEBATE

The standard of care provided to fatigue clients varies dramatically. It’s not a straight-forward condition like, say, a torn rotator cuff, generally is. There is no simple protocol that you can follow. A lot of patients have not tried Graded Exercise Therapy, or failed. This, again, as discussed in Part 1, may be due to the overwhelming disaccord of information.

An example of this is the statement from the leading community organisation advocating for ME/CFS in Australia, Emerge Australia (2017): “Exercise may be possible with ME/CFS, provided the program is based on an understanding of PEM [Post Exertional Malaise], and includes appropriate safety measures” however then concluded “…the lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of the treatment, GET programs should not be considered an appropriate treatment for ME/CFS.”

This contradicts both the Cochrane Review and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners:

“Patients with CFS may generally benefit and feel less fatigued following exercise therapy and no reliable evidence suggests that exercise may worsen outcomes.”

“Surveys by patient groups have suggested that GET may be harmful to some people with CFS. However, this finding is believed to be due to inappropriate exercise programs, possibly undertaken independently or under supervision from a person without appropriate experience.”

However, in the position statement Emerge Australia published in 2018 rather than advising against even considering GET as they did the previous year, they stated: “Emerge Australia warns of the potential for harm when GET is prescribed in a way that does not consider the nuances of PEM* and the individual patient’s health status and illness severity.”

Therefore, more recently, it appears there is a stronger consensus of the potential benefits, however, due to higher risk of exacerbating symptoms acutely, the combined GET approach is often avoided, rather than seeking appropriate and experienced professionals.

The Cochrane Review is the most trusted body producing systematic reviews of health research, so we are prioritising their recommendations, although with a heed to the warnings that Emerge presents.

MANAGING FATIGUE – THE BARE MINIMUM

A basic fatigue management program should involve managing the subjective symptoms. The common and necessary approaches to do so involve recording, assessing and planning activities using an Activity Diary and focusing on Activity Pacing, Graded Exercise Therapy and Lifestyle Habits. This is usually combined with Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, and consideration of pharmacological intervention.

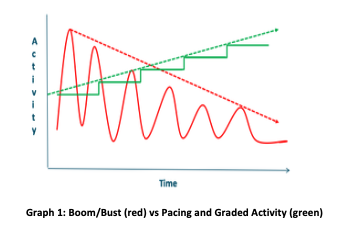

Activity Pacing aims to avoid the “Boom-Bust” cycle (i.e. doing too much, ‘crashing,’ repeating). See the Resource List at the end of the article for some great tips and worksheets. Activity Pacing is best supported with an Activity Diary to record and assess the current activities and then plan accordingly.

Graded Exercise Therapy involves establishing a physical activity baseline and progressively increasing the grade through duration, and then intensity. A GET supervisor needs to take daily and weekly Activity Pacing into account.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is most commonly used, and encourages the client to question the interpretation of their symptoms and therefore avoidance behaviours. Acceptance Commitment Therapy has been getting more attention lately and is worth keeping an eye on.

Modifiable Lifestyle factors that can assist in avoiding accidental exacerbation of fatigue symptoms. This includes sleep quality, nutrition, chemical sensitivities, environmental factors and stress management. Emerge has some good tips here: Managing symptoms on a daily basis and you can read up on our sleep tips here: What’s Your Sleep Score?

MANAGING FATIGUE – SUPERIOR

Superior management includes the above, but also adding some relative objective data, such as a more detailed Activity Diary, including rating the energy/fatigue level of each activity via a colour code. The benefit of this allows clients to physically see boom and bust pattern as they see the blocks of colours. This also makes it easier plan activities throughout the day to schedule ‘time-off’ and avoid blocks of high-energy activities. St. Helier & Sutton CFS Service has a great example of an activity diary (full with instructions) and the treatcfsfm website provides some examples of ways to visualise and understand allocating energy to activities.

In addition to the Activity Diary, implementing further physically objective restrictions such as a Heart Ratemaximum and a minimum-maximumStep Countcan assist in avoiding PEM. PEM, aka Post Exertional Malaise is defined as the exacerbation of some or all of an individual’s ME/CFS symptoms that occurs after physical, cognitive or emotional exertion. It can be a delayed response (usually 12-48 hours post exertion) and the symptoms can be prolonged (up to a week), and may be considered an extreme example of booming and busting.

A step count range can assist in monitoring and adhering to a total of (physical) activity throughout the day and allowing for measurable increases when appropriate. The relevance of Heart Rate restrictions is important to manage the intensity level of daily activity. Studies have shown chronotropic intolerance in CFS patients (the heart rate does not respond appropriately) therefore, to avoid PEM, it is recommended that the heart rate should not exceed moderate intensity (50-70% Max Heart Rate).

This data should be used to ensure baseline and the appropriate progressions – this is why you may see Activity Monitor Bands on our funding requests!

MANAGING FATIGUE – SPECIALISED HEALTH

At Specialised Health, we are doing all the above where we can, PLUS sourcing even more objective data, and focusing on a few extras.

#1 We are using Heart Rate Variability technology to assist in accumulating objective data of physiological fatigue to support the subjective symptoms.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is the variation in the time between each heart-beat. The raw data is most often presented as the rmssd number (root mean square of successive difference), though most mobile phone applications convert the reading into “Recovery points.” These numbers represent the action of the nervous system – whether it is appropriately upregulating (fight or flight) or down regulating (rest and digest) in response to external stimuli, or stress. Stress can be physical, cognitive or emotional or a mix.

So, in other words, we are measuring the body’s capacity to deal stress, ideally before the stress occurs and before symptoms would have risen. Consequently, we are helping prevent increases in fatigue and PEM, if the information is used appropriately with GET and Pacing. The HRV measurement also assists in educating clients in Boom and Bust behaviours as well as giving them the confidence to either rest or progress when appropriate. If the results are inconsistent with their symptoms or the activity diary, it offers an opening into further discussion about other barriers they may be either unaware of, or withholding.

⏩One of our clients had her life literally turn around using HRV and HR techniques. Prior to this she was exploring extreme options to deal with her fatigue, when we left her she was looking into preparing for work. She was so ecstatic she shared her experience with us on video, which you can watch here.

For our fatigue cases, other factors we focus on include:

- Develop appropriate and meaningful goals (setting of functional goals, for example, related to work and ADLs rather than just pure “exercise”). We often use the Patient-Specific Functional Scale to assist in developing goals as well as monitoring their improvement.

- Work closely with Rehab Providers; many Rehab Providers I have worked with have also been impressively skilled in goal setting, motivational interviewing, lifestyle interventions and education. With a similar approach it is essential we are providing consistent information and support.

- Conduct an extensive initial assessment to establish activity tolerances and baseline, barriers, and clear goals.

- Commence with frequent supervised sessions in order to monitor PEM and observe any inconsistencies.

- Continue awareness of, and support to improve, lifestyle factors that can impact HRV such as sleep, nutrition and environmental factors, emotional distress, menstruation cycle.

Prescribe relevant and individualised activities. For example, I had a client who was predominately restricted by cognitive fatigue and her work involved a great deal of comprehension. Increasing her fitness would help of course due to the benefits of GET as well as the benefits exercise elicits in the brain, however specific cognitive exercises could not go amiss, so she was prescribed time to exercise here: https://readtheory.org/.

Biara Webster

Exercise Physiologist and Writer

For more follow Specialised Health

RESOURCES

- Nutrition advice

- Full/Detailed Patient Self-Help Information

- Self-help advise

- Self Management, Work book

- Other helpful work sheets and planners:

- Activity Diary example and instructions

- Self-Help Course

REFERENCES

- S Eyssens, (2017), Post-exertional malaise (PEM) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome ME/CFS), Emerge Australia

- Larun et al. (2017), Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome, Cochrane Systematic Review

- RACGP (2015), Graded exercise therapy: chronic fatigue syndrome,Handbook of Non-Drug Interventions, RACGP Clinical Resources

- Emerge Australia, (2018), Position statement – graded exercise therapy.

- J Bavington, et al., Manual for therpaists, graded exercise therapy for cfs/me, on behalf of the PACE trial management group

- A Martin et al., (2019), Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for ME/CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) – A feasibility study, Journal of Contextual Behavioural Science, Vol 12, pp 89-97

- L Chu et al., (2018), Deconstructing post-exertional malaise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a patient-centered, cross-sectional survey, PLos ONE 13(6): e0197811.

- T Davenport (2019), Chronotropic intolerance: an overlooked determinant of symptoms and activity limitation in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome?, Front Pediatr, 7: 82

- G Bjørklund et al., (2019), Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): Suggestions for a nutritional treatment in the therapeutic approach, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy vol 109, pp 1000–1007

- M Uhde (2018), Markers of non-coeliac wheat sensitivity in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, Gut, Vol 68 No 2 (Post Script Letter)

- https://www.hrv4training.com/blog/heart-rate-variability-hrv-and-the-menstrual-cycle