Semantics

“Bone-on-Bone” generally refers to the condition of Osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a “disease” of the joints which results in narrowing of the joint space through articular cartilage degeneration and consequent parts of the bone thickening. For a recap, articular cartilage is the connective tissue at the end of bones which decreases friction between the bones during movement.

“Disease” is in inverted commas because the process is actually highly associated with ageing, and ageing is yet to be classified as a disease. The term “disease” is also often used inappropriately, as they incorrectly associate the disease with symptoms. The experience of symptoms is usually termed “illness.”

Why is this relevant?

Because it affects the definition of the condition. And the definition affects the understanding and the understanding effects the patient’s sense of control.

Many definitions you will find online of Osteoarthritis will include pain, however, pain is not experienced by all people with the condition. This may encourage the client to believe that the pain is a part of the disease and there’s nothing they can do about it.

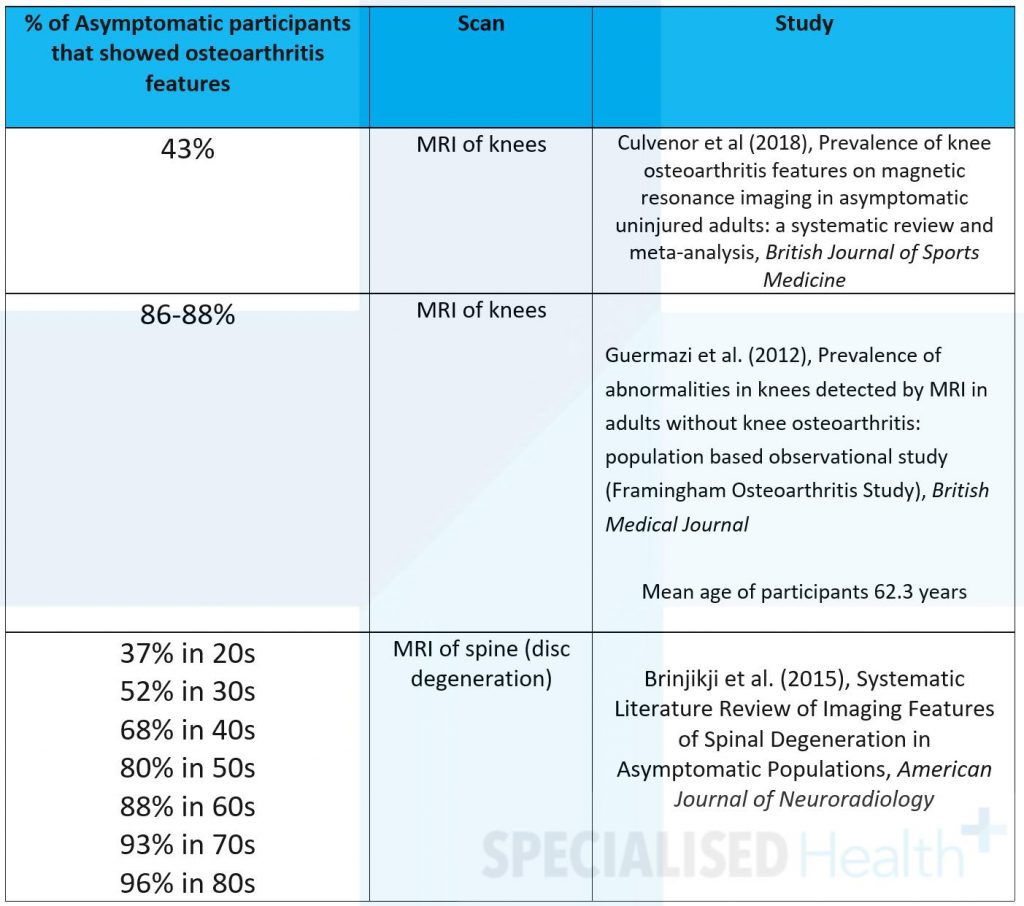

But, in fact, many people have osteoarthritic changes in their joints, according to scans, and don’t even know it. Here are just a few examples:

It’s a simple IQ test:

All* patients with joint pain & changes have OA but not all people with OA have joint pain.

*Not actually all, but to simplify the statement, pretend that’s true.

This then begs the question, is the disease causing the pain? That, is not a simple question and requires a complex answer, which we won’t go into today.

Causes

So, what causes Osteoarthritis then?

As mentioned, it’s believed to be a normal process of ageing, although some can experience it earlier than others. Apart from being on the planet for another revolution around the sun, other risks reportedly include genetics, obesity, previous injuries and repetitive or heavy vocations.

Although, from the recent science the last few are debatable. Some studies have shown that age is correlated with knee osteoarthritis, with no differences between BMI groups, although it may depend more so on body composition.

And injuries don’t guarantee OA, rather the consequences of the injury may, i.e. biomechanical ‘bad habits,’ movement and loading avoidance!

Huh? – E. Wellsandt et al. (2016) wrote that researchers have found OA in ACL patients who don’t load (don’t take the weight) through their knee and no OA in ACL patients who do load their knee properly!

They explained that cartilage in the knee increases in thickness in response to higher repetitive loading during walking. Walking in a manner that decreased load through the knee resulted in cartilage thinning!

So, the philosophy of adapting and growing when challenged isn’t just reserved for self-help books. Literally, our body responds to stimuli. The correct amount of stimuli increases strength, in the muscles and bones, and also, in some parts of the body, cartilage! We need exercise!

Newer research is also showing a significant role of inflammation in the OA process and the importance of inflammation management through dietary and other lifestyle influences.

Pain and Disability

There is no denying that pain is associated with osteoarthritis, in some people. Like any condition really, it’s the symptoms that get in the way of life. In the case of OA this is usually pain and stiffness. To avoid these symptoms, usually people start to avoid particular movements, especially physical activity. Which of course then results in loss of strength and mobility (and as just mentioned, usually plays a hand in progressing cartilage loss, making it worse!).

OA & Specialised Health

Yes, OA is associated with injuries, whatever the pathophysiological reason may be. So, this is why it’s quite common for us to see, whether it be the primary condition or a comorbidity.

We can’t fix it but we can definitely help. Here’s what we do:

Exercise!

Bet you didn’t expect that!

Of course you did, but we want to help you understand why.

- This is a cool word: mechanotransduction

It’s basically the process mentioned previously: the physiological response of the body, on a cellular level, to mechanical loading. This is the process by which bone, muscle, tendon and cartilage strengthen. And reverse, the reason for deconditioning, where you lose strength without the stimuli to respond to.

So,

- (Again) Strengthen muscles, bones and joints so the body can have the strength get back to doing normal life things, and prevent worsening progression of the disease.

- Exercises to improve flexibility and range of motion, i.e. mobility.

- Exercises to improve biomechanics (how the joints are moving and taking load)

- Exercise to assist pain tolerance

- Exercise to assist weight loss (which decrease pressure on the joint and potentially assists in inflammation control)

- Exercise to prevent other health conditions

It is essential that all the exercises are performed within the individual’s pain tolerance and progressed appropriately.

Education and Behaviour Change Support

We provide education on activity pacing to work within the body’s current tolerances, to not overdo things which causes flare-ups, and of course, the role of exercise.

We provide education on pain management including management strategies and also basic neurophysiology to help understand the pain side of things. This also includes definitions of the condition and reconsidering the use of words (e.g. is saying “bone-on-bone” an empowering, helpful choice of words?). The combination of exercise with exercise can help modulate perceived sensations and safety.

With the role of inflammation in the development and progression of OA, we also provide education on other lifestyle factors such as the impact of drinking, smoking and nutrition (good thing we have a Dietician).

Biara Webster

Exercise Physiologist and Writer/Content Manager, Specialised Health

Resources

RTW SA has some great resources, particularly:

- https://www.rtwsa.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/112324/What-you-need-to-know-about-scans-activity-and-pain.pdf

- https://www.rtwsa.com/service-providers/pain-management

- https://www.rtwsa.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/112378/Spinal-imaging-chart-for-web.pdf

References

- Elizabeth Wellsandt et al. (2016), Decreased Knee Joint Loading Associated With Early Knee Osteoarthritis After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury, Am J Sports Med. 2016 January ; 44(1): 143–151. doi:10.1177/0363546515608475

- Khan & Scott (2009), Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists’ prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair, British Journal of Sports Med;43:247–251. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.054239

- V Byers Kraus (2015), Call for Standardized Definitions of Osteoarthritis and Risk Stratification for Clinical Trials and Clinical Use, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2015 August ; 23(8): 1233–1241. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.036

- Lepestos & Papavassiliou (2016), ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis, Biochimica et Biophysica

- Mathiesen & Conaghan (2017), Synovitis in osteoarthritis: current understanding with therapeutic implications, Arthritis Research & Therapy 2017 19:18, DOI 10.1186/s13075-017-1229-9